Bruckner: Symphony 1

Perhaps it is telling Bruckner's first handful of symphonies are set in a minor key. The minor mode has an inherently built-in sense of drama, a wonderful way for beginning symphonists to hook their audience.

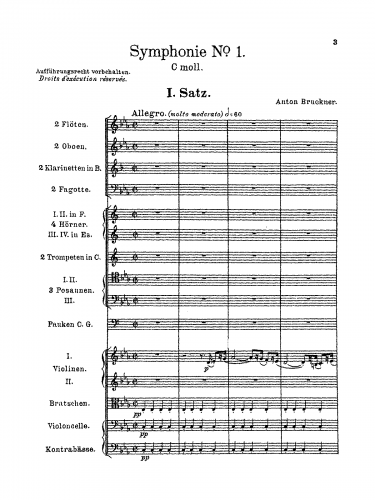

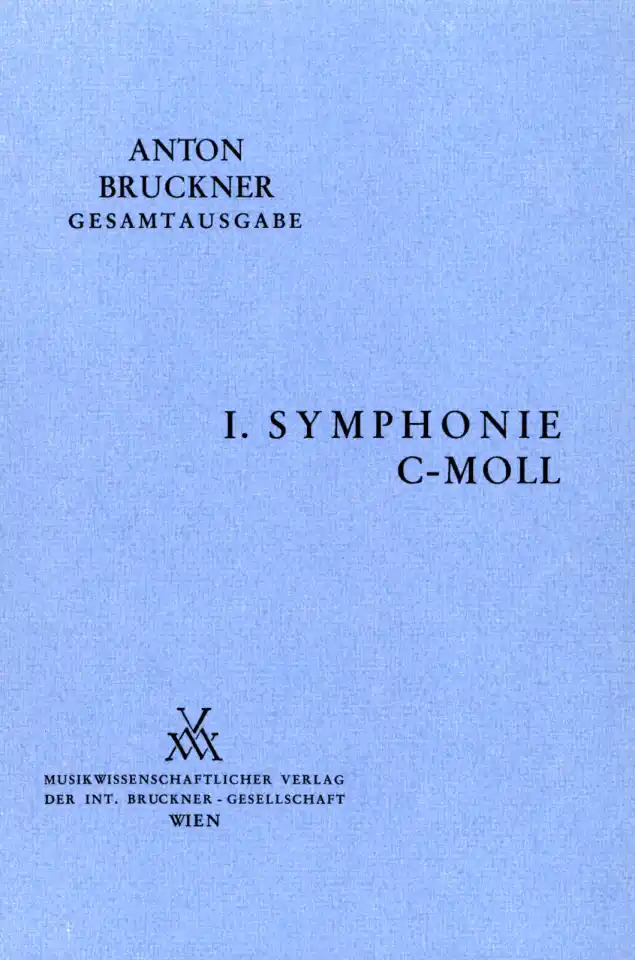

But before I head into the music, I should mention the editions. Symphony no. 1 in C minor is one of the easier to track. Most recordings tackle the Linz edition, either edited by Haas or Nowak. Between those two editions, differences are minimal, at least compared to Bruckner's later symphonies.

There is also the later Vienna version, which is the most different. It is not one I enjoy as much, but with many orchestras and conductors now trying to record every edition, it has a solid base of recordings as well.

I should also mention Bruckner's subtitle 'The Saucy Maid' or 'The Cheeky Lad'. I can't say the name fits well, but I am sure whatever the purpose was in the 19th Century, it was worth adding.

I like Bruckner's First Symphony, if nothing else, than for how it gets down to business. The first movement throws the listener right into its opening with little in the way of atmospheric introductions, the last movement bursts right out into declamatory statements with little pretense, and the Scherzo is one of the composer's finest. That really only leaves the wandering second movement holding onto its mysteries. At a 45 minute runtime though, there is little time for Bruckner to waste.

I love the first movement's grouchy opening march, one that vies as the most memorable motivic material of the work. If you like the music of Richard Wagner, the third theme, announced without any shame by the trombones in a wide-leaping motive, is straight from the Wagner-ian playbook. There are little of the Bruckner-ian pauses or sectionalism present, but the music is ably developed.

What I notice most as I listen, is the first movement's rhythmic disparity. The dotted-sounding rhythms of the trenchant march is often played against straight quavers, while overlapping duples and triples are found throughout at well. This will actually continue into the second movement as well.

Speaking of the second movement, chromatic harmonic ambiguities litter its beginning. It takes until 2 minutes in before we get a sense of cadence, and on towards three minutes until something song-like comes along, finally settling into a key center. A this point, I notice those rhythmic oddities, where Bruckner sets the violas in moving quintuples, while sextuplets and triplets mix amongst straight quavers. Bruckner writes this all in a way which flows gently and smoothly, so I doubt anyone would notice such things. Plus, the second section plays things rhythmically straight in comparison.

Strife is generally kept to a minimum in the second movement, though. In a few places, the music suggests darker futures, but the music always turns away towards lush, wind-laden pastoralisms. For me, this movement wanders far more than I enjoy, although I appreciate the strong arrival point towards the end of the movement.

If you are looking to hear a solid Scherzo from Bruckner, there is no better place than to start here. The third movement is terrifying with its orchestral hits and gnarly minor-keyed crags. The tune is super, one which would be an excellent addition to a fantastical tone poem or the like. The contrasting Trio contains gentle horn pipings and wind burblings, a prime example of the effectiveness in Bruckner's mood settings without harmonic chromaticism getting the way, instead working hand-in-hand.

The bold storminess of the fourth movement is an unusual start to a finale from Bruckner. The composer usually holds back showing his cards until later. Unlike Mahler, who preferred a symphonic journey from dark to light, I rarely sense such a path from Bruckner, who seemed to like a more fragmented approach to the symphony. This last movement, however, could be considered as such. There is certainly a dichotomy between minor and major, often jutting back and forth.

Symphony no. 1 in C minor is still Bruckner trying to find his way, though. His structures are generally easy to follow, which is great for a listener like me; I don't like to be left at the wayside. Yet, the hallmarks of Bruckner's later symphonies have not quite developed. The First Symphony is certainly a progression from what came before, though, sometimes startlingly different.

As far as recordings are concerned, I don't need a grand mystical vision in this music. And yet, below I list recordings from the great European orchestras as some of my favorites. Only Solti is the odd one out, and he isn't has brusque with the music compared to the later symphonies. On the other hand, Karajan is not the be-all end-all for his approach, as he didn't take with these early symphonies other than to fill out the set, not that Berlin and Karajan are ever poor partners in the early works. They just aren't as essential or all-consuming in this music.

1965: Jochum

1981: Karajan

1985: Sawallisch

1995: Solti

1998: Barenboim

2024: Poschner (1865 Scherzo)

For

now, we will have a

very basic list of Bruckner reviews above. Those recordings I mentioned

as an example in the text above, or performances I have come to respect

which await future reviews, are listed above in greened bold. My actual reviews can be found in the typical Oozy Keep orange. Until we at The Oozy Channel Keep

have gotten ourselves up and running, this should suffice and we can

reorganize the page a little more coherently in the future.