Haydn: Symphony 88 - 92

Paris Symphonies: Part Deux. That is what I have entitled these five symphonies.

The last three of this symphonic quintet were commissioned from the same ensemble the actual Paris Symphonies came from. The first two were sent to Paris to cement his popularity in the Gallic country.

And yet, it seems these five works find Haydn back to his old comfortable style of composing. Without the need to impress through a visit to a foreign country, Haydn is much more relaxed, where his humor and developmental digressions run full steam ahead.

I'm not sure why these five weren't all grouped together with the Paris Symphonies. Both volume 6 and 7 are only two CDs each, and previous volumes have contained many more discs. Perhaps, dollar signs were involved...

One movement type I want to mention regards the Minuet. Whereas, this section is usually considered a throwaway dance movement, Haydn is really making something of them, even if their music has become more for the concert hall than the dance hall. The composer has been working on making the second section of the Minuet much more developmental, visiting foreign keys and using fragmented ideas to cohere this area of music. While many would list the Minuet and Trio as their least favorite aspect of a Haydn symphony, as least there is a sense of direction and evolution in the master's compositions.

Let's get to the numbers:

Nicknames

Oxford (92)

Not much in the way of named symphonies, yet there are only five symphonies in this volume.

Opening Tempo & Tempo Markings

Slow Intro: Four (88, 90, 91, 92)

Four out of five! Not only is the slow introduction becoming more prevalent, its relationship with the following fast tempos are becoming more important.

With Symphony no. 90, Haydn no longer changes the time signature between the slow introduction and fast tempo proper. Before, if the slow preamble was in duple, the fast exposition would be set in triple, and vice versa. Not so with Symphonies 90 - 92, where the time signature remains the same throughout. I will be curious to see if this choice continues into London.

This leads me to the important bit. Haydn is making the slow introduction an integral part of the exposition. While the traditional Classical Symphony usually begins the moment a fast tempo arrives, Haydn begins melding the two, where the fast tempo continues what the introduction set up, delaying the start of the exposition until after the fast tempo has already begun.

It seems a small thing, especially in the last century-and-a-half where invention has sped up to a manic pace. Yet, I imagine Haydn had to test his ideas with audiences of specific tastes and needs. These were folks not necessarily interested in abrupt changes outside of their comfort zones, music included. After all, it has taken ninety symphonies for Haydn to get this far.

As to tempo markings, most slow introductions are set at Adagio, although one of the rare Largo markings appears (another is seen in a second movement). That takes my total to six.

Instruments

Trumpet & Timpani: 88, 90, 92

Interestingly, trumpet and timpani are brought into Symphony no. 88 at the second-movement position, a portion of the symphony where those instruments usually tacet.

Initial Time Signatures

3/4: Three

4/4: One

2/4: One

Symphonies 90 - 92 all begin in triple meter; the composer usually liked to mix up his starting time signatures. From my view, this allows Haydn to set the second and fourth movements in his preferred duple meter, laying the 3/4 Minuet betwixt them.

Title Key Signatures

Sharp: Two

Flat: Two

C Major: One

Minor Key: Zero

Homotonal: Zero

Haydn has grown into the rhythm of changing home keys in the second movement only. Usually this is to the Dominant key, although in this group of symphonies, C Major moves to the Sub-Dominant.

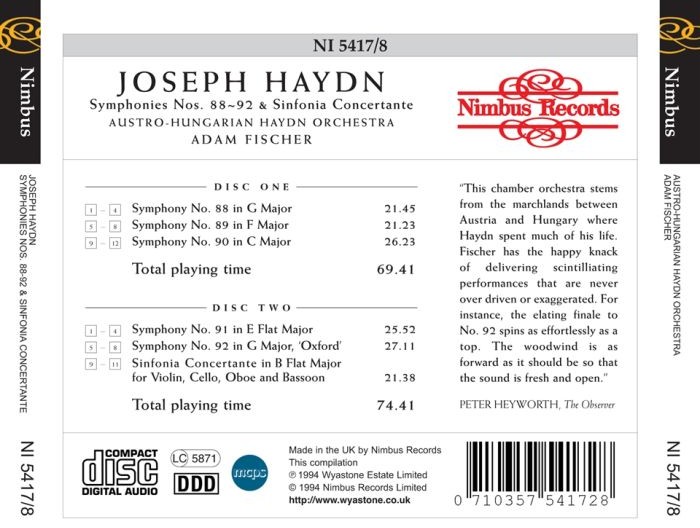

Length

Ádám Fischer's longest symphony runtime, from Nos. 1 - 92, is now Symphony no. 92, which nearly reaches 27 minutes. This one also has the longest Minuet and Trio movement, not far from reaching six minutes; the final Presto is pretty lengthy in the scheme of things as well.

With the beginning comes swampy acoustics. It is as if the Austro-Hungarian Haydn Orchestra is playing in a shopping mall performance area or a parking garage. To use this metaphor, the strings are allocated the prime handicap spots, while the winds are in the further metered spaces. The poor flute sounds like it was confined to a distant, lightly urinated-upon moped hidden nook.

And yet, this is how the music most likely sounded to Prince Esterházy. I understand the popular, later symphonies were recorded first, trying to initially draw consumers in, but had they realized their engineering abilities and musical approaches would change so much over time, I am sure this project would have ended up sounding much differently for these later works. Oh well... my ears adjust just fine over time.

Find more Haydn recordings HERE!

Comments

Post a Comment