Haydn: Symphony 88 - 90

If I recognize Haydn in passing, I am not one who can say exactly what work and what movement it comes from. That is not how my mind works, for it wishes to puzzle rather than know.

Symphony no. 88 in G Major is one of those. The second and fourth movements bear melodies which are very well known to me, even if I don't necessarily place them within this work immediately. But, I will get to that later.

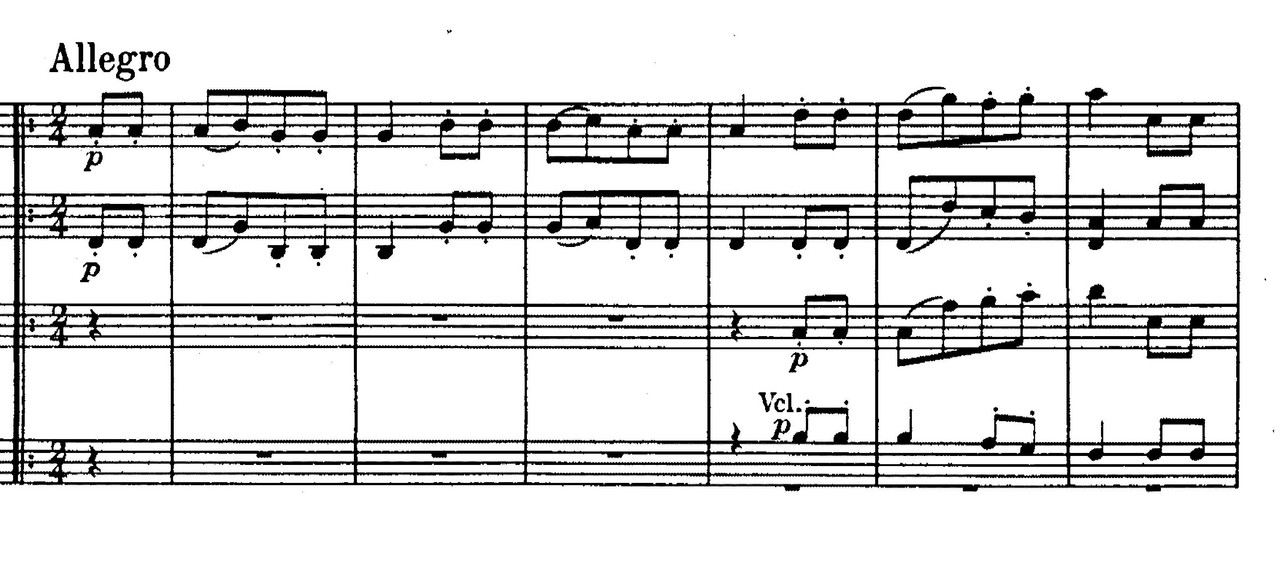

When we arrive at the Allegro proper, after the slow Adagio introduction with chromatic figurations, a pert little theme takes the listener away. This theme is a perfect example of how Haydn so successfully builds his themes too:

A short, seven note motive, made up of three intervallically close notes are stated across two bars, then it is repeated, but at a whole note higher over the next two measures. Finally, a melodic send-off takes the phrase to its highest point over two bars, only to take the music back down where it began across two bars, but with the addition of some fancy note decorations, symmetrically ending the melodic phrase over eight total bars.

And that is just the first theme. Haydn begins this motive on just the two violin parts, adds the rest of the strings two bars in, and then the winds join to finish off the eight-bar phrase. For the restatement, because after all we want the listener to remember this music for later development, the whole ensemble plays together, while the lower strings have a rhythmically offset bit of interest leading downward, away from the melodic motion.

I love breaking down these little tidbits every once in a while, if nothing else than as a reminder that while this is music which sounds easy on the ears, these are also expertly crafted musical ideas when expert musical craftsmanship wasn't necessarily a given in the above terms amongst other composers of Haydn's day. And he does so so effortlessly. I haven't even really gotten to the interesting stuff yet either!

Here is a symphony scored for trumpets and timpani, and Haydn doesn't even utilize them in the first movement. A curiosity for sure! After the melody I spoke of before concludes, a transition section which is both more furious sounding and much longer follows. The second theme isn't as obvious, although if one follows the lack of semi-quavers, the difference will lead ears to the correct place.

As has been usual with Haydn, the recapitulation is more developmental and interested in linking to the Coda rather than completely restating everything verbatim once more. Compared to the other symphonies I have heard from Haydn recently, this opening is a little shorter comparatively.

The second-movement Largo is all about its romance melody on solo cello and oboe, one of the composer's very finest. While this is a theme and variations form, Haydn isn't as interested in mucking about with the melody all that much, preferring to keep it in its relatively original state. Instead, its surroundings change with each appearance.

And surprise! The trumpets and timpani show up in the second movement, a portion these two instruments usually aren't involved with at all. They arrive at one of the loud contrasting episodes, leaving the luxurious lush beauty alone.

So, the Minuet and Trio used to rely on the Trio for its contrast. Lately, however, Haydn has used the second section of the Minuet as a sort-of developmental area to wander off to far flung keys, only to return to the original for the Trio. Of course, the Trio isn't straight forward - Highlander drones set under violin and wind melody making.

At one point in my youth, I lived with Leonard Bernstein's Vienna recording of Hob. 1:88, particularly the last movement. But, the correlation isn't nostalgic, as now my memory is imbued with Bernstein's conducting (I will post the video at the bottom). If you haven't seen it, the US musician stops conducting, only to use his eyes, with the camera right on him. He was very much a conscious performer.

In any case, the fourth movement contains another wonderful melody, one which is perky and delightful, almost as much as it is witty and pastoral. A short surge into the minor is just as memorable as its turn back to the main tune and key.

Groups of three short notes seems to be the rhythmic motive of Symphony no. 89 in F Major. In this case, I am actually more fond of the second theme, a legato, scalular idea which Haydn doesn't afford much time to. One time with violins and another for the oboe and a short transition leads to the development.

After some stormy noodling, unusually placed rests lead to an abrupt transition to the recapitulation, another of the developmental type, for the composer lands in D-flat Major of all places. Fun, but strange; or another one of Haydn's false recapitulations. It is so hard to tell sometimes.

What appears to be a ternary-form second movement begins with a lilting feel, although Ádám Fischer doesn't particularly take to either the Andante or con moto tempo directions. His is slower and more intimate, perhaps to better contrast with the 'B' section in C minor.

The Minuet and Trio opens with a fanfare on winds only, answered by the whole ensemble, and finished off with strings and flute, the latter absent at the opening statement. This sort of mix and match approach is effective in Haydn's hands, for its keeps the music from becoming stale or too similar. A light dance feel underlines the Trio, with combinations of flute, oboe, and bassoon matching the violin on melody.

The unusual musical term strascinando makes an appearance in the last movement, one which tells the players to stretch out the beats a little. Fischer and the Austro-Hungarian Haydn Orchestra already do this to some degree, usually in the Minuet and Trio, where the last beat in a measure is given a little extra time. To my ears, it lends a folk rusticity to the proceedings, where musical character is always welcome.

Haydn changes the key signatures from F Major to B-flat Major and back, and later on to F minor and back to the home key. The textures of the last contrasting episode sounds texturally more complex to my ears, offsetting the main idea very well indeed. Fischer adds a surprising cadenza towards the end, quite a flourish which made my eyes open wide.

Symphony no. 90 in C Major's slow introduction is only unusual in relation to the Allegro which follows. At this tempo intersection, Haydn acts as if he is finishing off a melodic idea in the first four bars right at the start of the fast section. This makes it seem to the listener that the main theme began in the slow movement, but was finished off in the fast transition, something the composer doesn't do. Upon restatement and quotations later in the symphony though, this simple cadential finish ends up being the actual musical idea proper, short and unmelodic though it be. Short rests divide up the music right at the very end of the first movement, showing Haydn's wit toying with listener expectations.

The composer bandies between F Major and F minor keys, using the two differing ideas as a launching point for two different sets of variations. In the second section of the third-movement Minuet, oboe and flute go back and forth with one another, while the oboe alone is the main focus of the Trio. At nearly six minutes, this now may be the longest Minuet and Trio of Haydn's symphonies thus far.

Since the third movement is becoming more essential to the symphony in size and scope, a portion typically reserved for a dance, the musical development is becoming much more of concert-hall interest rather than as a dance form.

I will spoil it right away - the joke in the concluding movement of the symphony involves a four-measure rest. For those musicians counting the music, this can seem like an eternal amount of time, and to the audience, it sounds like the end of the work. No, there's more!

These symphonies between the earlier Paris Symphonies and the later London Symphonies were recorded around 1990 & 1991. At this time in their Haydn project, it is the flute which receives the brunt of the billowy acoustic at Palace Esterházy. Too bad, since the flute has so much play time in this music, especially as it often has to pair with violins in this music. The flute is ably heard, yet its quality is watery and distant in relation to the strings.

On the other hand, the oboe is appreciably forward, wonderfully portrayed in Hob. 1:88, while the bassoon is right there along with them. Horns get little to do outside of adding color, while the trumpet and timpani work their magic.

Works

Symphony 88 in G Major, Hob. 1:88 (21.45)

Symphony 89 in F Major, Hob. 1:89 (21.23)

Symphony 90 in C Major, Hob. 1:90 (26.23)

Performers

Austro-Hungarian Haydn Orchestra

Ádám Fischer, conductor

Label: Brilliant Classics

Year: 1990-91; 2002

Total Timing: 69.41

Symphony 88 in G Major, Hob. 1:88 (21.45)

Symphony 89 in F Major, Hob. 1:89 (21.23)

Symphony 90 in C Major, Hob. 1:90 (26.23)

Performers

Austro-Hungarian Haydn Orchestra

Ádám Fischer, conductor

Label: Brilliant Classics

Year: 1990-91; 2002

Total Timing: 69.41

Find more Haydn recordings HERE!

Comments

Post a Comment