Haydn: Symphony 82 - 87

While there were a handful of symphonies written by Haydn outside of his employ before now, suffice to say, the six symphonies composed for a commission in Paris represent a remarkable step forward for the composer.

This step forward doesn't only refer to his broader success outside of Austria, but also in Haydn's stretching the form of the genre.

Where in the last volume of symphonies on Nimbus I noted a gentleness creep into the outer movements of his works, for Paris, Haydn brings back the contrasting loud portions in a more obvious manner. His symphonic expositions are fit to bursting, with two contrasting themes and full transitions between them, and the developments and recapitulations are in no hurry to conclude.

At the start of the Paris Symphonies, I thought I clawed in on some extra use of chromaticism, however, I either forgot that train of thought while listening, or it was simply applied here and there. Certainly, Haydn is not afraid to go further afield in searching out far-flung keys in the developments, but also to really search out ways to apply his melodic ideas.

The Theme and Variation form has really set into the second movement position, while the Rondo has settled into the fourth movement. The Sonata-Allegro form is of course part of the first movement, expanded some by Haydn in this set of symphonies, and variants of that form are mixed into the Rondos as well.

I do not detect as much overt humor from Haydn either, although I am sure closer inspection would reveal more. The rests and pauses are the most apparent moments, especially when the silence sounds out uncomfortably long. The composer has instituted musical effects to appease the pleasure of his French audiences and court, so there are different musical dynamics at play as well.

While there are only six symphonies in this set, let us see where the numbers lie across the sextet:

Nicknames

The Bear (82)

The Hen (83)

The Queen (85)

About half were given nicknames, albeit post Haydn. I could also include In Nomine Domine for Symphony no. 84, as spurious as that title is.

Opening Tempo & Tempo Markings

Slow Intro: Three (84, 85, 86)

Of course, the numerical Hoboken numbers are not chronological, so these symphonies weren't necessarily composed one right after the other. Hopefully, this is a trend of Haydn's beloved slow introductions.

Two Largo's appear, one in an introduction of Hob. 1:84 and another for a second slow movement in Hob. 1:86, paired with the term Capriccio. This is only the second time Largo has been used in the second position, although a total of four overall, by my count.

Instruments

Trumpet & Timpani: 82 & 86

Trumpet and Timpani remain the outliers of visiting timbres in Haydn's symphonies. It should be noted, the composer was requested to write for an expanded string section in Paris, but I am not sure what the requirement was regarding winds. Suffice to say, flute and bassoons are now a common, consistent element in his orchestrations.

Initial Time Signatures

3/4: Two

4/4: Three

2/4: One

Two of the slow introductions are set in a triple-meter time signature, not included in the short list above; instead I only use the tempos proper. I will say, it seems Haydn tries hard to contrast his starting movement meters from symphony to symphony. Never do I hear the same thing over and over again.

If there is anything curious, a 12/8 time signature appears in the final Vivace movement of Symphony no. 83. I have really only seen that applied once in a symphony, also in a final movement.

Title Key Signatures

Sharp: Two

Flat: Three

C Major: One

Minor Key: One

Homotonal: Zero

Every symphony in this set moves to the Sub-Dominant more consistently in the second movement, the other being the Dominant. In a minor keyed symphony, he generally moves to the Relative Major after the first movement.

As with the most recent minor-keyed symphonies from Haydn, the composer isn't interested in holding onto that mode past the first movement. Again, in this case, he moves out of G minor within the first movement, to end in the sunnier G Major.

As has become a trend, the Minuet and Trio third movement retain the home key the whole time with no contrast in the Trio. Instead, he uses differing instrumental textures to vary the sound with the same key. It should be said, these dance movements have become longer as well.

Length

And not just the Minuet and Trio. The whole run of any individual symphony is consistently expanded in length in this volume. The first movements are most noticeably longer, the second movement theme and variations make those portions substantial, and with the slightly prolonged Minuets, these symphonies regularly time longer. Only the final movements seem resistant to protracted lengths, even in their Rondo forms.

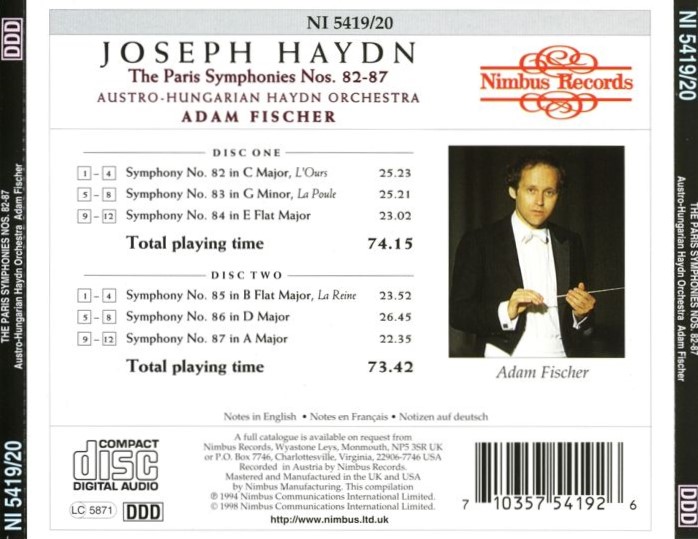

Ádám Fischer usually observes the first-section repeats, but not the second (aside from the Trio, of course). This might make timing comparisons quite different between recordings. Where each Brilliant Classics Volume contains three symphonies, they generally time just over or under 60 minutes. These two volumes of the Paris Symphonies both approach the 75 minute mark, showing the expansion of Haydn's symphonies is bright light.

All this means is the acoustic is a little more watery, with the winds a tad further back. Fischer occasionally will add an offbeat accent for interest, and generally I enjoy his phrasing dynamics as opposed to a literal translation with none attached.

Otherwise, these are straight-ahead interpretations from the Hungarian conductor and his orchestral crew. I'm sure I have also become comfortable with their playing style and the Nimbus sonics.

Find more Haydn recordings HERE!

Comments

Post a Comment