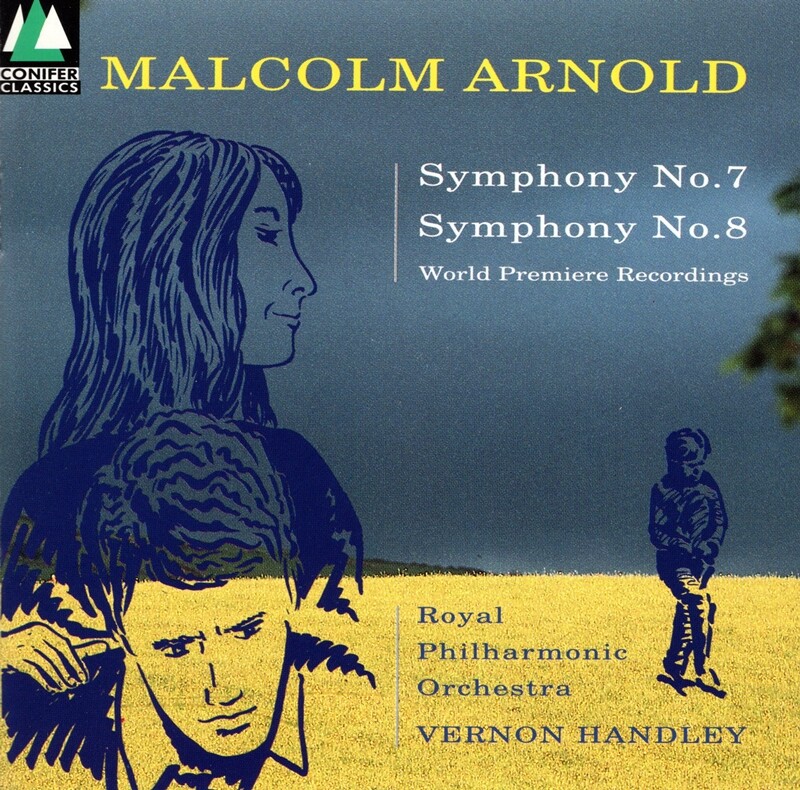

Arnold: Symphony 7 & 8

Harrowing.

That is the first word which comes to mind after listening to Sir Malcolm Arnold's Symphony no. 7.

Such a word is even more surprising, since each movement was written as a portrait of one of his children. If it was claimed the composer was dealing with personal demons, this symphony is a prime example of such a statement equated to his music.

A musical idea of three instruments playing in close intervals is unnerving, but so is the Oom-Pah device which is spread throughout the first movement. A more lyrical, lamenting theme later on is almost a balm for the listener, despite its ingrained melancholy. Only a brief, eerie jazz outburst smack dab in the middle offers any wit, and it is sardonic at that. A sort-of manic telegraph rhythm infests the final third, making a textural change while also amping up the sharp rhythmic qualities already announced. All of the players get a fair workout in the lengthy opening movement, where the lack of significant percussion outside of bass drum and timpani makes the music sound rather oppressive, try as the harp might to give some humanity.

The second movement is almost as long as the first. While there are a few tempo changes noted in the title of this track, they don't occur until the last few minutes. Too bad, for this music could use some relief, at least for this listener. On the other hand, a significant trombone solo plays across this movement, here credited as Derek James, making for a welcome change in texture and focus. Whatever faults I may have with the heavy mood, no one could accuse Sir Malcolm of not being bale to effectively handle an orchestra for a listener across 30 minutes or so. I feel like in other circumstances, Arnold may have added a vibraphone in this middle movement, but the composer strips the music bare, opting instead for the unusual tones of bongos, toms, and congas alongside brass smears.

If anyone thought a final movement Allegro would turn things around like they did in his Sixth Symphony, think again. Only in the last moments of the work does Arnold hint at folksy rosiness. The bright presence of piccolo, harp, and chimes achieves this turn in orchestral timbres, plus an unexpected final exultant major chord takes everyone by surprise.

I usually mention a filmic, cinematic element in Arnold's music, but the thought doesn't come as quickly to mind here. Perhaps the more uncomfortable moments of a Hitchcock film or the like could be apt, but these would not be feel-good portions for sure. Instead, the composer walks the listener through a difficult emotional state, one that is raw for all to hear and certainly not easy to face. My thoughts go out to all who live particularly hard lives and hope they can find a modicum of peace when they are able.

Vernon Handley and the RPO do not buff any of the music's edges, laying out all of the tumult and modernism for the listener to experience first hand.

Arnold builds on the idea of childhood rosiness by taking a march tune and making it appear a handful of times throughout the first movement of his Symphony no. 8. The tune, though, appears in an echo form the first few times, almost as if it is being relived through nostalgia surrounded by darkness rather than being experienced in the here and now.

Some caustic rhythmic qualities fill up much of the opening movement as well, sometimes taking up a militaristic quality parallel to the friendly march tune. It is the orchestration choices which make this portion seem lighter than its earlier symphony brother; the piccolo, the harp (who shares a short unusual duet with the timpani), and the spacing of the vertical harmonies lead me to such thoughts. A later statement of the happy march tune reminds me of Arnold's orchestral Dances, yet not completely devoid of uncertainty either, although the final statements fully arrive to satisfy the tune for the listener, albeit with a hushed close.

The middle movement presents more solace at first, at least more than the previous symphony. However, the music devolves into uncertainty as it develops, particularly in the string writing. Again, it is the piccolo, harp, vibraphone, and celeste/glockenspiel which offer some bright color here, and I appreciate their presence. Later he overlaps these particular instruments with brass, and it is quite an effective moment. Otherwise, Sir Malcolm chooses chamber-like textures here, preferring small amounts of instruments at any given time, over instances of full ensemble, making for a rather intimate scope overall.

The lively third and last movement opens with boisterous motions, exhibiting more of the traits from Malcolm Arnold I have come to enjoy. A sort-of lounge act segment in the middle with pitched percussion is the kind of unexpected qualities I relish. In his communication with the Albany Symphony Orchestra, for whom this symphony was to premier, he promised a 'spring-like' character, and I do indeed get that feeling, even if it isn't rampant throughout.

How often does one sit down and revisit Schindler's List? Not I, thus I think I will be more apt to visit Symphonies 4 & 8 from Arnold compared to the emotionally tougher Symphonies 3 & 7. I can't call them works I enjoy less, however, I really have to be in a very certain state of mind to even appreciate some of Arnold's works in a listening session. I suppose, that is what makes them timeless artistic pieces of art which evoke humanity in all of its forms.

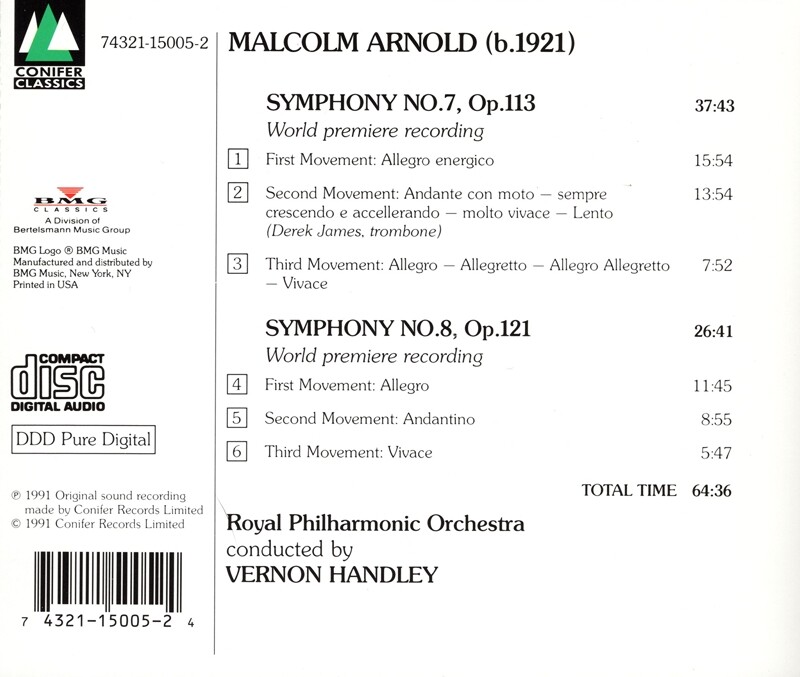

Works

Symphony 7, op. 113 (37.38)

Symphony 8, op. 124 (26.42)

Performers

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Vernon Handley, conductor

Label: Conifer

Year: 1991; 2006

Total Timing: 64.38

Find more Arnold recordings HERE!

Comments

Post a Comment