Handel: Messiah

What is a Classical Music blog without an entry dedicated to G.F. Handel's Messiah? Not much of one, methinks.

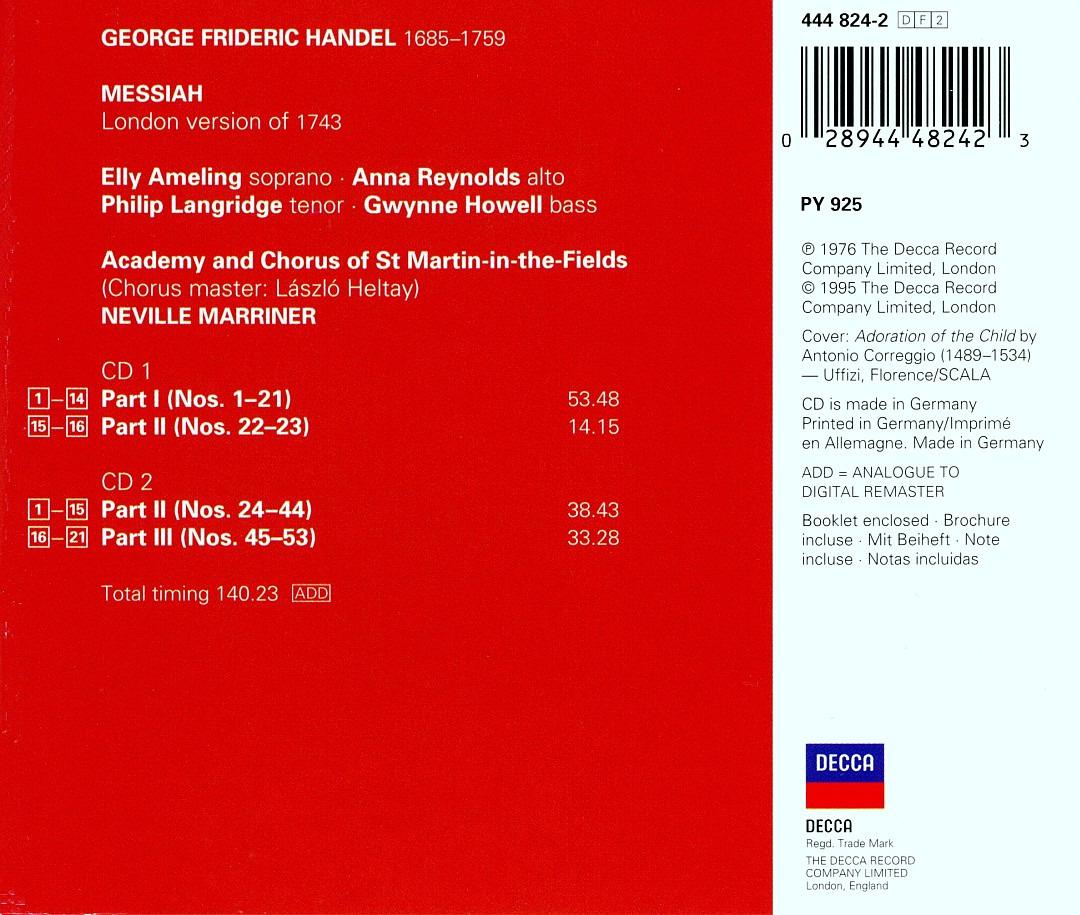

Of old-school recordings, this is a favorite. Of Marriner's recordings, this 70s performance is better than his later one, a preference of mine from the conductor in general.

It should be noted that this recording performs the 1743 London version of Messiah, and I spell out the differences in the review below, along with more specific elements regarding this particular recording.

Despite these differences, I love the soloists here, and the chorus is excellent. Marriner goes for a half-HIP approach, before such a label could be placed upon it. This recording and one from Sir Colin Davis around the same time are stalwarts in the Messiah catalog for good reason.

I might not care to visit Messiah all too often, for the work is a long, not too interesting oratorio that is ubiquitous in my area around the Yuletide season, usually in an abbreviated or truncated form. Yet, many of the solos and choruses are simply excellent from the composer, and the few orchestral numbers are worthy of remembering. Thus, the recording comes out every once in a while.

A review from 2019

This 1976 performance of Handel’s Messiah is led by Sir Neville Marriner and his Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields orchestral and choral forces. It is important to note that Marriner uses Christopher Hogwood’s edition of Messiah from the first 1743 London performance. This creates only a few differences than most might be used to, but easily trumps Hogwood’s own later performance from the early 80’s through sheer energy and abilities on display. Decca's recording came in direct competition with 3 or 4 high-profile Messiah recordings from the previous decade and Decca provided Marriner clear, pétillant sound at St. John’s, Smith Square in comparison to those 60’s recordings.

The Orchestra: These are sparkling performances all around. Marriner and the Academy orchestra are virtuosic and magnetic, with bouncy, transparent textures that are warm in their use of modern instruments, but are crystal cut in their direction from Marriner. Marriner moves the opening Overture in a dance-like forward motion, but is a fully satisfying sound, and that is just the Sinfonia. St. Martin-in-the-Fields gives enough weight without sounding stodgy nor anemic, but gladly puts down the accelerator, especially the choral movements, while lovingly embracing the more intimate moments.

The Chorus: Marriner’s choral movements are truly allegro when marked so and the choral forces have crystal-clear lightness and sharp-edged preciseness in the swift portrayals of ‘He Shall Purify’, ‘For Unto Us’, and ‘O We Like Sheep’, for example, but are blazingly full-bodied in ‘His yoke’, ‘Hallelujah’, and Worthy is the Lamb’. Marriner is deft enough to not rush ‘And the Glory of the Lord’, giving weight to the triple meter without rushing into a beat-to-the-bar which sinks many runaway tempos of modern period performances. The Academy chorus sopranos use little-to-no-vibrato in typical English style, I personally prefer a more symphonic chorus approach, but I like the lack of old-Germanic wobbliness, and their clear textures allow the chorus amazing flexibility in the faster passages. The chorus is well heard in relation to the instruments.

The Vocalists: The soloists are a solid lineup on this recording. The highpoint is Philip Langridge’s clear, effortless tenor, with precise diction, and whose sound does not bleat in typical English tenor fashion. Langridge’s ornamentations are small, tasteful, and purposeful, and never takes away from the written music. Dutch soprano Elly Ameling is bit more dramatic, with more operatic portamento guiding her vocal movement, but giving much more character than the rest of the team. That said, Ameling’s ornamentation is the more distracting of the soloists, with some intrusive choices, but her singing is welcome here. I was initially reticent of Welsh bass Gwynne Howell’s enormous vocal production, a bit off-putting on first hearing in the over-melismatic ‘But Who May Abide’, but I eventually found delight in his upper range, one that has a particularly glorious ring that easily sets him with the best bass singers on ‘The Trumpet Shall Sound’ for sheer forceful drama. Alto Anna Reynolds is a bit Plain Jane to me, but she is rather sensitive in the lengthy ‘He was Despised’.

The Continuo: Lastly, the basso continuo of cello, harpsichord, and organ is delightfully unintrusive; that jangly harpsichord can turn me off of so much Baroque music rather quickly if too forward in the sound, and here it is perfect. I greatly prefer organ as my continuo, so I appreciate its heard, additional presence in the sound; plus you get the authority of Christopher Hogwood on the organ continuo here. The trumpets are properly bright and cuts through in ‘The Trumpet Shall Sound’ and choruses.

The Differences: There are a number of small differences with the 1743 London edition: the extra bars of music in the opening ‘Every Valley’ are hardly worth mentioning, but always catch me off guard. More noticeable is the compound meter (12/8) of ‘Rejoice Greatly’ that can be very disconcerting if you have only heard the simple meter (4/4) version, but is a pleasant difference. And of course for every aria/recitative and duet, Handel provided 2-4 alternate versions for other voice ranges and vocal combinations in different keys, but there were a few arias I associate with a higher tessitura singer but here was sung by a different voice part; the difference is negligible for me.

The Choices: From the era this recording was made, this was considered a period performance. But since today’s recordings use period instruments and railway-tragedy speeds, Sir Neville Marriner’s performance now holds the middle ground between the weighty stodginess of the big orchestras and the wheedly, vinegary sounds of original instruments. At the time, Marriner came in direct competition with Sir Colin Davis and a pared down LSO on Philips , a very good performance with starry soloists, and Sir Charles Mackerras with the Ambrosian Singers on EMI . These are still good performances and certainly provide relevancy today, and I think my initial preferences lie with Marriner and Davis for sheer excellence. If you wish to go truly old school, Eugene Ormandy and Philadelphia on CBS are big boned with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, Robert Shaw on RCA was influential for its time, and Sir Thomas Beecham on RCA/Sony has an amusingly over-Romanticized recording. If you wish to meet the modern era, I really like the late Sir Richard Hickox on Chandos with his solid adult chorus, but much goodwill has also been given William Christie on Harmonia Mundi , McCreesh on Archiv , as well as the older Pinnock and Hogwood, but I don’t care for the piping boy-choir sound in those Handel choruses.

Conclusion: This recording of Sir Neville Marriner’s Messiah performance features excellent orchestral work, lightly swift, but appropriately full-sounding choral work, a solid team of vocal soloists, and clear, full sound from Decca. I think this recording will duly satisfy both the average listener looking for their first complete Messiah as well as the collector looking for outstanding performances of this seminal work.

Works

Messiah, HWV 56

Soloists

Elly Ameling, soprano

Anna Reynolds, alto

Philip Langridge, tenor

Gwynne Howell, bass

Performers

Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields & Chorus

Sir Neville Marriner, conductor

Label: Decca

Year: 1976; 1995

Total Timing: 2.20.23

A favorite recording of Messiah for this listener, although not the only one I enjoy.

I could see the differences of this 1743 London version rubbing some the wrong way, yet how interesting Handel included so many ways to perform the same song.

Comments

Post a Comment