The Symphony: A Prelude

So, I have decided to begin listening to all of Haydn's symphonies chronologically. The composer has 104 numbered symphonies to his name, plus some others cataloged a little differently, so determination is needed to traverse them all.

Making such a choice is akin to watching Gone with the Wind, Lawrence of Arabia, or Schindler's List. These are great, even perhaps important pieces of media. Yet, as a watcher I need to have a predetermined amount of time and be in the right state of mind, setting me up for a successful watch or listening session.

With a title such as Father of the Symphony, as well as Father of the String Quartet and Father of the Sonata, Haydn's genres are calling to be explored. I am probably more familiar with his string quartets as a genre than the symphonies, thus I think it is time to visit them all.

I know many of Haydn's symphonies from Antal Doráti's complete set with the Philharmonia Hungarica. Similarly to Karl Böhm in Mozart's symphonies, which I will also need to cover at some point, Doráti could be leaden in tempos, especially in the endless minuets. Plus the Hungarians could be in rough sound too.

And so, I am excited to hear the complete set from Ádám Fischer which was set down in the mid-to-late 80s through the early 2000s with the Austro-Hungarian Haydn Orchestra, all recorded at Esterházy Palace in Austria. I believe Fischer started up another set with the Danish Chamber Orchestra shortly afterwards, as his first set was accused of poor sound for some of his earlier performances. We will see...

I suppose some words should be spoken regarding the Symphony as a genre, although I do not claim to have even an ounce of intelligence nor insight compared to the world's very worst musicologist.

There is a wonderful quote from Howard Goodall (or his BBC script writer) about the symphony as a genre, when introducing Haydn's role in what will become a very popular music form:

It was

like an essay, or an exceptionally long doodle. [...]symphonies were to

be explorations, a journey to find out what would happen if you took a

few tunes and mucked about with them. For sure, the symphony is a

peculiar thing - 60 musicians simultaneously interpreting instructions

given to them by one person, with no narrative, no plot, and no literal

meaning; nor is it generally a description of anything. Just four

loosely related seven-or-eight minute sections of meandering music at

slightly different speeds, strung together for the thought-provoking fun

of it.

The odd thing about the symphony is, at this point in history, it doesn't have any direct parallels in any other artistic field. It's abstract, more than 120 years before the concept became fashionable in visual art. The Story of Music - Age of Elegance.

The odd thing about the symphony is, at this point in history, it doesn't have any direct parallels in any other artistic field. It's abstract, more than 120 years before the concept became fashionable in visual art. The Story of Music - Age of Elegance.

I know the Baroque model settled on a tripartite form for its Orchestral Suites, Concertos (both Solo and Grosso), and Sinfonias. You can hear this in Mozart's opera overtures, where there is still a fast-slow-fast multi-movement form in existence.

While Haydn certainly didn't invent any of these genres, he certainly solidified their structures, the use of rondo and sonata-allegro form, and the four-movement model. Since he was a revered personality, many looked to how he was composing symphonies, sonatas, and string quartets, thus creating a musical, albeit German, tradition.

Like those Baroque forbears, Haydn begins his symphonies in the three-movement form, eventually resting on the four-movement one. It took him until Symphony no. 30, if not further, to put this aspect behind him once and for all.

Haydn's symphonies were never lengthy affairs; Mozart and Beethoven would take more energies to expand the genre. Each work lays generally between 15 to 25 minutes in length, keeping the overall package closer to a Baroque Suite or Concerto. From Symphony no. 31 on, Haydn will reach towards the over-20 minute mark, putting more of an emphasis on structure and development. Once you get to Haydn's last handful of symphonies, the composer has reached the apex of the genre.

In a symphony, I generally appreciate first movements most, mainly for their tight structures, as I am a formalist at heart. I like the grounding of thematic devices for the listener before the composer has their fun through the development. Often the second movement is the soul of the symphony, usually through a songful setting, contrasted through a moderate third-movement dance. Often the final movement is lighter than the first in substance, but could also be a riotous send-off for the listener. At least this is the blueprint which the Romantic Era picked up.

While I consider Mozart the master of melody, Haydn was certainly no slouch in this department. He essentially formed a consensus on the shape and motion of a motive, balancing expectations for the listener. What I remember most from Haydn is his invention of orchestral color, especially as it relates to winds and percussion. He was certainly in more of a position to take chances as a composer, imbuing no small degree of wit and knowing looks into his music, often subverting listener expectations.

Of course, Haydn's most popular symphonies are the named ones; bearing a subtitle is a publisher's dream after all. There are sets of symphonies which are well liked too, such as the minor-keyed Stürm und Dräng symphonies and the later Paris and London symphonies. Coming back to what I am going to listen to, it is in these symphonies where Ádám Fischer will have a harder time competing, for these works are well-recorded by the great luminaries of the 20th-Century orchestra.

But I am looking forward to my time with Haydn's symphonies under Fischer. As I said, my memories are mostly with Dorati and his heavy-footed minuets, so I doubt I will be let down by this set.

I know I am behind the times by covering this Brilliant Classics box. Many more sets have since appeared, including period-instrument traversals and reissues of old ones. But recordings aren't meant to be held in their own time in my mind. They are eternal, so whether I write about these in 1987, 2001, or now, these symphonies are meant to be listened to - music's whole purpose of existence.

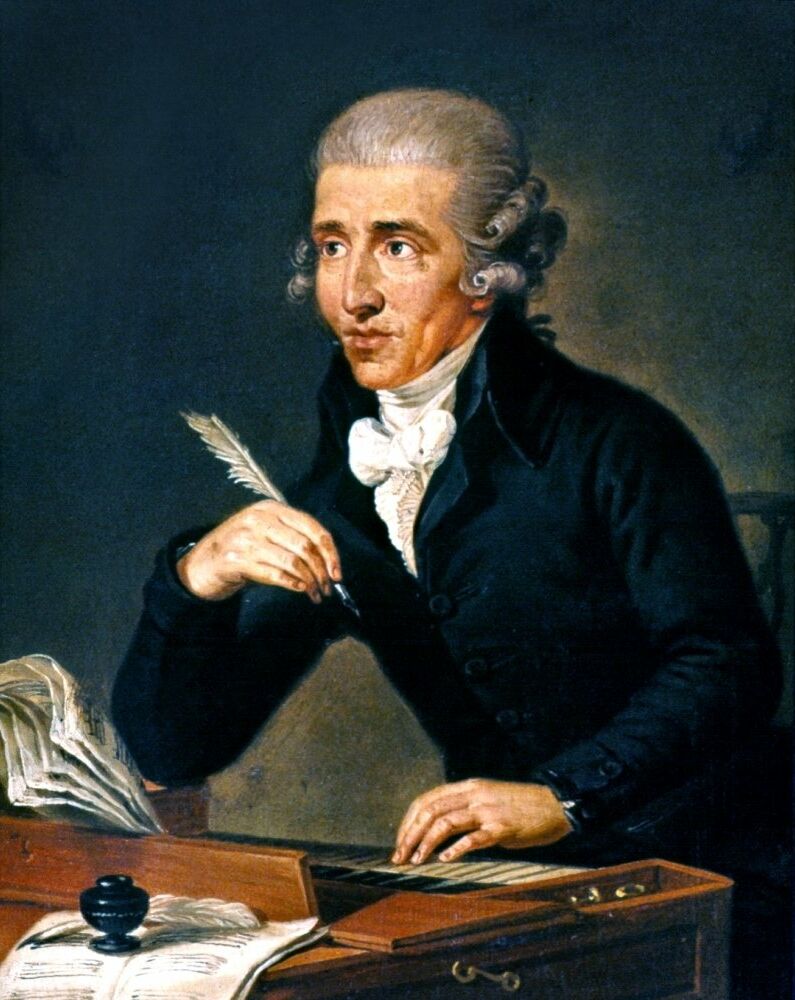

_-_Franz_Joseph_Haydn_(1732-1809)_-_RCIN_406987_-_Royal_Collection.jpg)

/Symphony2018_Logo_RGB.1c3c866fd07d8eb7cb9bfbdbdc8a9cf08bcd83dc.png)